حسام الدین شفیعیان

وبلاگ رسمی و شخصی حسام الدین شفیعیانحسام الدین شفیعیان

وبلاگ رسمی و شخصی حسام الدین شفیعیان/یکشنبه نخل/

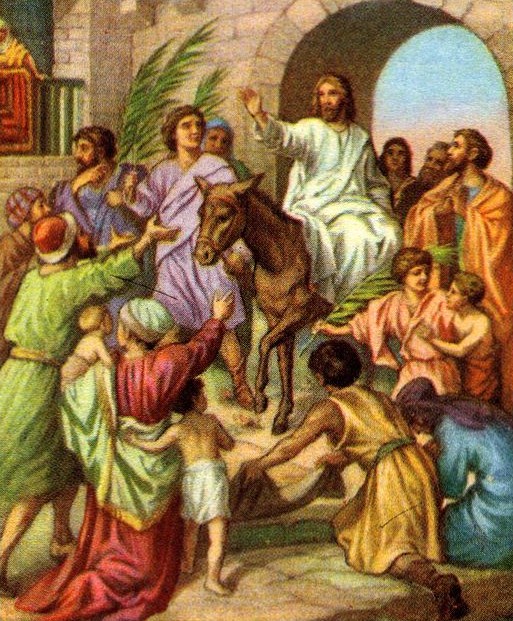

یکشنبه نخل یا عید شعانین یا عید سعانین عیدی مسیحی در یکشنبهٔ قبل از عید پاک و شروع هفته مقدس است. این عید، نماد ورود عیسی به اورشلیم، در تمام اناجیل اربعه ذکر شدهاست (مرقس ۱۱:۱–۱۱، متی ۲۱:۱–۱۱، لوقا:۱۹:۲۸–۴۴، یوحنا ۱۲:۱۲–۱۹). علت نامگذاری نخل بر آن این است که هنگام ورود عیسی به اورشلیم مردم با شاخههای نخل به استقبال وی رفتند.

عیسی در بازگشت پیروزمندانه به اورشلیم در یکشنبه پیشاز عید پاک، بهجای اسب که نماد پادشاهان بود، سوار بر الاغ، نماد صلح وارد شهر شد.[۱][۲]

/Ash Wednesday/

Ash Wednesday is a holy day of prayer and fasting in many Western Christian denominations. It is preceded by Shrove Tuesday and falls on the first day of Lent[2] (the six weeks of penitence before Easter). It is observed by Catholics in the Roman Rite, Lutherans, Moravians, Anglicans, Methodists, Nazarenes, as well as by some churches in the Reformed tradition (including certain Congregationalist, Continental Reformed, and Presbyterian churches).[3]

As it is the first day of Lent, many Christians begin Ash Wednesday by marking a Lenten calendar, praying a Lenten daily devotional, and making a Lenten sacrifice that they will not partake of until the arrival of Eastertide.[4][5]

Many Christians attend special church services, at which churchgoers receive ash on their foreheads. Ash Wednesday derives its name from this practice, which is accompanied by the words, "Repent, and believe in the Gospel" or the dictum "Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return."[6] The ashes are prepared by burning palm leaves from the previous year's Palm Sunday celebrations.[7]

Ash Wednesday is observed by numerous denominations within Western Christianity.[8] Roman Rite Roman Catholics observe it,[note 1] along with certain Protestants like Lutherans, Anglicans,[8] some Reformed churches,[11][12] some Baptists,[13] Methodists (including Nazarenes and Wesleyans),[14][15] the Evangelical Covenant Church,[16] and some Mennonites.[17][18] The Moravian Church[19][20] and Metropolitan Community Churches observe Ash Wednesday.[21] Churches in the United Protestant tradition, such as the Church of North India and United Church of Canada honour Ash Wednesday too.[22] Some Independent Catholics,[23][24] and the Community of Christ also observe it.[25]

Reformed churches have historically not observed Ash Wednesday, nor Lent in general, due to the Reformed regulative principle of worship.[26][27][28] Nevertheless, some churches in the Reformed tradition do observe Lent today, although often as a voluntary observance.[29] The Reformed Church in America, for example, describes Ash Wednesday as a day "focused on prayer, fasting, and repentance."[3] The liturgy for Ash Wednesday thus contains the following "Invitation to Observe a Lenten Discipline" read by the presider:[30]

/ Cyclopes/

A cyclops (meaning ‘circle-eyed’) is a one-eyed giant first appearing in the mythology of ancient Greece. The Greeks believed that there was an entire race of cyclopes who lived in a faraway land without law and order. Homer, in his Iliad, describes the Cyclopes as pastoral but savage, typical of the strange creatures the Greeks created to represent foreign societies not regarded as civilised as themselves. The Cyclopes are not without talents, though, and are credited with manufacturing the thunderbolts which Zeus used as a terrible throwing weapon and as the builders of gigantic fortification walls such as those still seen at Mycenaean sites today. The most famous cyclops is Polyphemus, who captured the Greek hero Odysseus and his men only for them to escape by blinding the poor giant. Cyclopes, and particularly the Odysseus story, were popular and enduring subjects in all forms of Greek and Roman art.

/Cyclopes/

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, the Cyclopes (/saɪˈkloʊpiːz/ sy-KLOH-peez; Greek: Κύκλωπες, Kýklōpes, "Circle-eyes" or "Round-eyes";[1] singular Cyclops /ˈsaɪklɒps/ SY-klops; Κύκλωψ, Kýklōps) are giant one-eyed creatures.[2] Three groups of Cyclopes can be distinguished. In Hesiod's Theogony, the Cyclopes are the three brothers Brontes, Steropes, and Arges, who made for Zeus his weapon the thunderbolt. In Homer's Odyssey, they are an uncivilized group of shepherds, the brethren of Polyphemus encountered by Odysseus. Cyclopes were also famous as the builders of the Cyclopean walls of Mycenae and Tiryns.

From at least the fifth century BC, Cyclopes have been associated with the island of Sicily and the volcanic Aeolian Islands.